Guidance for Reporting and Writing About Racism

Reporting beats, or specialized subjects that a journalist will stick with day in and day out, become sections in the paper and separate pages on a website. Sports, travel and tech news are clearly delineated to the eye, but those divisions are often blurrier than they appear.

Julian Glover, adjunct faculty at the Newhouse School and Race & Culture reporter at ABC7 San Francisco, says it is difficult to fully untangle the implications and history of race from every other beat.

“We can really look at all of those different slices of life, those different sections in the newspaper, and then overlay this lens of race and culture and say, ‘What else is happening here?’” Glover said. “‘What might we be missing by just reporting on the initial headline of the story?’”

For example, coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic is incomplete without addressing the disproportionately negative impact the pandemic has had on Black, Hispanic and Native Americans.

It is why every reporter, regardless of background or beat, should be able to report and write about racism.

Hub Brown, a former associate dean at the Newhouse School who worked on efforts to enhance diversity in the school’s faculty, staff and student body, says that a journalist’s first obligation is to the truth, not a section of the paper.

“When a journalist ignores the racial implications of something, say, the effect of systemic bias on a particular issue… you basically ignore the kinds of things that are pressures that prevent people from maybe achieving those sorts of things,” Brown said. “Then, you’re not being truthful.”

But the likelihood that newsrooms will prioritize these stories is often contingent on the diversity of existing staff—and in U.S. newsrooms, that staff is largely white and male.

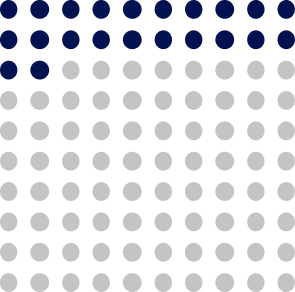

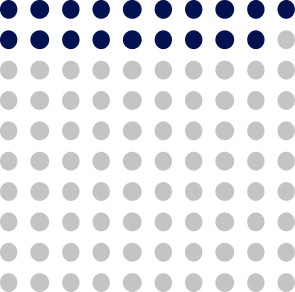

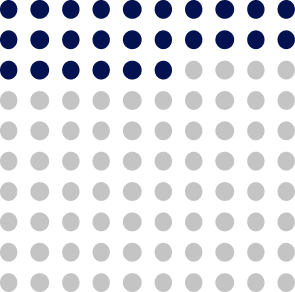

Racial and ethnic minorities are about 40 percent of the U.S. population, according to the Census Bureau. However, they comprise less than a quarter of newsroom staff, according to the 2019 ASNE Newsroom Diversity Survey.

In 2019:

22% of salaried employees in newsrooms were people of color

19% of newsroom managers were people of color

26% of news organizations have a non-white person in one of the top three newsroom leadership roles

Data is from the 2019 ASNE Newsroom Diversity Survey. The ASNE survey relies on newsrooms to report their staffing statistics by the end of the year and had a 22.8% participation rate in 2019.

The gap between readers and reporters could widen, as the nation diversifies faster and is projected to be minority white and majority BIPOC by 2045, per Census projections. And newsrooms are more than two decades past the proposed deadline for demographic parity by 2000, made by the American Society of News Editors in 1978.

ProPublica reporter Topher Sanders explained how the whiteness of news organizations can affect coverage and communities in a 2020 conversation with the Knight Foundation. He proposed this question: “When those [predominantly white teams] are your gold-standard reporting teams within an organization and they lack diversity, what types of projects will be pursued?”

“It’s a no-brainer that when you have diverse thoughts and perspectives, it shows up in the work, and it starts to show up in the community,” Sanders said. “Lots of times, the work generated from investigative reporting has real impact.”

Newsrooms, reporters and their leaders should consider diversity at all levels, including how they hire talent, make assignments, and write stories.

Five Considerations When Reporting and Writing About Race and Racism

Conversations with professors Glover and Brown provided some guidance for writers encountering common questions when reporting and writing about race—from seemingly small decisions around word choice to more conceptual questions regarding how we perceive others.

These considerations are not exhaustive. They should be used in tandem with other resources such as experts, organizations working toward newsroom diversity and anti-racism leaders.

Mitigating Personal Bias

As Brown describes it, writers learn to write from their own perspective. An unintentional consequence is that the perspective of those who matter to the story can be lost along the way.

Those who experience privilege due to their race, gender or class cannot live the experiences of those without privilege. Those blind spots, biases and the lens through which a storyteller sees the world matter: These are what frame the subject and readers’ perceptions of it.

Danielle K. Kilgo’s research on protest coverage highlights how instances of reporting bias can snowball into larger differences in how certain communities are portrayed. Kilgo’s data shows that coverage of the Women’s March and anti-Trump protests were more likely to legitimize protests and explore their grievances.

In contrast, protests against anti-Black racism and in support of Indigenous people’s rights were more likely to be described as threatening and violent. One framework centers the experiences of those protesting, the other pushes those experiences to the periphery of the story.

Consider

- Better understand your own implicit biases. Writers can begin with tactics to identify and reduce your implicit biases from the American Academy of Family Physicians, including individualization and mindfulness. Additionally, Project Implicit offers an Implicit Association Test to educate the public about biases and help people begin to recognize their own perceptions.

- Do your homework. “Do some deep research on the topic that you’re reporting on,” Glover said. “Unlearn the incorrect or improper history that you knew, or learn the full history that really connects the dots in a throughline that explains what a particular community might be going through.”

Identifying the Story

Coming up with a new story, especially under the pressure of a day turn, can be stressful. But those pressures should not lead to shortcuts.

“My biggest fear is to go to someone in a particular group with an idea of what I think is the most important thing to this group and essentially telling them that this is the story,” Glover said. Instead, reporters hope to build relationships with people so they can learn what the real story is and what the community wants amplified.

Consider

- Solicit ideas from the community and build a rapport with local citizens. Glover promotes his social channels and email as a way for people to reach out to him with stories and has found that people are responsive.

The feedback loop continues after a story, too. Viewers have the opportunity to reach back out with follow-up tips or comments.

- Do not just highlight trauma within a community—uplift culture, different identities and intersectionality. Glover tries to offer solutions when he can. For example, a story on high suspension rates among Black, Latina and Indigenous young women also included information about the latest interventions to help reduce recidivism.

“I think in many communities folks are tired of hearing the statistics. They’re tired of hearing how bad it is because in many cases they know how bad it is,” he said. “What can we do about it? And how might the viewers who are watching us every night … get into and be a part of those solutions?”

Building Trust in the Community

Building a feedback loop requires participation, enthusiasm and trust between community members and yourself.

However, Americans’ trust in the media to report the news fully, accurately and fairly is at the second-lowest level since Gallup started measuring in 1972. About 36 percent of people said they have “a great deal” or “a fair amount” of trust in the media, according to Gallup’s October 2021 data.

Researchers, such as Online News Association President Mandy Jenkins, are trying to investigate where distrust in reporters is coming from. Jenkins hypothesized to The Pulitzer Prizes that it is not always partisan-driven—there are many people who see journalists come from outside the community, report a national story and then leave town.

Consider

- Make sure people are comfortable with your process and have clear expectations. “[That way] they don’t open up to you, they don’t share their space, their knowledge, their perspective and then see it boiled down to a five-second sound bite that doesn’t articulate what they were trying to convey with you,” Glover explained.

- Let audiences hear directly from the source. Although reporters are the experts at writing for the air or a newspaper, they are not the experts on someone’s lived experiences. “It’s oftentimes just so powerful to step back, listen and let people speak for themselves,” Glover said.

Writing in Active vs. Passive Voice

Active voice uses fewer words, is more direct and is easier to understand. It also requires the writer to identify an actor, which in cases of violence and racism can feel nerve-wracking.

A New York Times tweet from May 2020 describes three violent acts during Black Lives Matter protests. It also highlights the difference between passive and active voice. One part of the tweet reads:

Passive Voice

A photographer was shot in the eye.

In this sentence, the actor is hidden. Rubber bullets cannot shoot themselves, but writers do not need to name the perpetrator with passive voice.

Active Voice

Protesters struck a journalist with his own microphone.

The active voice here gives the reader a clear description of the actor and the action.

“Passive writing obscures blame, obscures responsibility. It’s why bureaucrats use it all the time,” Brown said. “‘Mistakes were made and others will be blamed.’ In order to refrain from doing that, you absolutely have to step up and say, ‘Yeah, this person did that thing.’”

Consider

Brown says that transitioning a sentence in these cases requires courage and exactness. You have to understand what you are saying and put in more work to be sure of it.

For example, in the sentence:

Protesters were hit by rubber bullets.

To publish this, the reporter only needs to confirm what happened but not how it happened.

To make the sentence active, additional reporting needs to identify actors, such as who pulled the trigger:

Police shot protesters with rubber bullets.

Brown recommends reporters have a clear understanding of which words convict and which words describe an event.

“I think that that’s one of the reasons why there is fear, because they think, ‘I’m trying him in a court of law.’ No, no, you’re actually talking about objective reality,” he said.

“It is not a matter of law or a matter of debate that a police officer killed George Floyd, that’s not up for debate,” Brown said. “What is up for debate is whether or not he did it in a premeditated fashion, whether or not he was reckless with disregard for his safety.”

Using the Word “Racist”

In January 2019, NBC issued guidance to their staff telling them not to refer to former Rep. Steve King’s comments about white supremacy as “racist.” Shortly after the email leaked, NBC revised the comment, but the incident highlights the fear around using the word.

Instead, headlines often use terms such as “racially motivated, “racially tinged” and “racially charged.”

In an episode of Code Switch, NPR’s Gene Demby said that it is difficult for journalists to describe a person or action as “racist” under the framework with which so many view racism. “If you primarily understand racism as a kind of illness of the soul—a moral failing—[then] you can’t use that term unless you can sort of characterize what’s happening in people’s hearts,” Demby explained. “We as journalists can’t really do that. But that’s not the only way to understand something as racist, right?”

Consider

- Avoid shorthand like “racially charged” and “racially motivated” in place of a description of an actual act. Lawrence B. Glickman wrote that these euphemisms first appeared in the 1950s and ‘60s—”racially tinged” is used to describe the explosions at a recently desegregated campus. Glickman’s data shows that these vague phrases became more frequent in the 1990s and have consistently been used in the last decade. He said that terms like this suggest that race is neutral and “make it difficult to speak accurately of racial oppression.”

- Confirm the act meets the definition of “racism,” without characterizing the actor’s motivation, and be as specific as possible, as recommended by The Associated Press. They also recommend avoiding describing an individual as “racist”—words like “xenophobic,” “bigoted” or “biased” could be more accurate alternatives.

Additional Reading and Resources

Below are some additional tools, style guides and articles to help writers further engage with the content:

- Race-Related Coverage, AP Style Guide: guidance from the Associated Press on when to mention a subject’s race, word choice for terms like “racist” and “racism,” and more.

- Conscious Style Guide: collection of style guides focusing on race, disability, age and more.

- NABJ Style Guide: guidance from the National Association of Black Journalists on racial identifiers and other terms that are of specific relevance to their community.

- Best Practices for Journalists Reporting on Police Killings of Black and Brown People, NABJ: includes discussions from image sourcing to highlighting the humanity of Black victims of police violence.

- “Decades of Failure,” Columbia Journalism Review: newsroom-specific diversity data that includes statistics on leadership.

- “How Diverse Are US Newsrooms?,” American Society of News Editors: interactive website with ASNE survey data. Visualizations show gender and race breakdowns against parity with each newsroom’s respective market.

Citation for this content: Communications@Syracuse, Syracuse University’s online master’s in communications.