Why Billionaires Keep Investing in Major League Sports

In the fall of 2012, Jimmy Haslam, a Tennessee billionaire whose father founded what’s now the Pilot Flying J trucking empire, walked into a meeting of NFL owners in Chicago and received a thunderous round of applause. Haslam had bought the Cleveland Browns for $1 billion and the members of the exclusive club he’d just joined were welcoming him.

“It’s very exciting,” Haslam told the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “Our entire family is very excited. It’s a great opportunity … we’re gonna do everything we can to bring a winning team to the Browns.”

These days, owners of professional sports team franchises invest not just for championships but also for returns. And they’re getting them. Haslam was right about his purchase of the Browns being a great opportunity. A little more than four years later, he’s already made an estimated $850 million on the Browns, a 16.6 percent annualized return. Investing in the S&P 500 SPDR exchange-traded fund over the same period yielded 10.6 percent.

Big Leagues, Big Wins

Haslam’s returns may be exceptional but they aren’t uncommon.

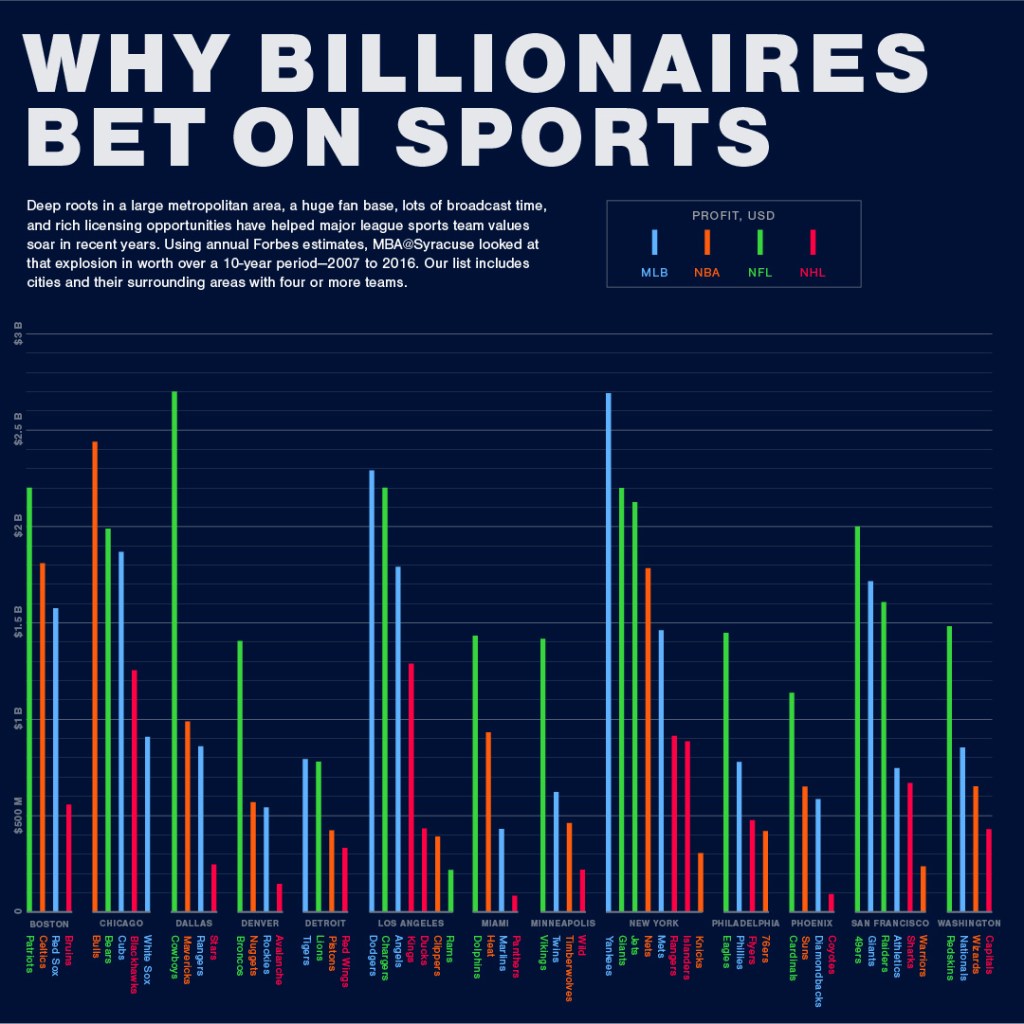

A look into the average value of professional franchises in the four major league sports shows consistent, across-the-board gains over the last several years.

Go to a text version of Why Billionaires Bet on Sports.

Alexander McKelvie, an associate professor of entrepreneurship at the Whitman School of Management who teaches in the MBA@Syracuse program, said there are a number of factors that make sports franchises such attractive financial investments.

Many major league sports leagues “have relatively favorable player union agreements, structured rules and revenue sharing agreements that all franchises need to follow, new arenas and stadiums with exclusive boxes, [and] greater customer experience focus at games,” McKelvie said. Perhaps most importantly, the leagues have “lucrative TV and sponsorship contracts that help to ensure that there is positive cash coming in. League expansion also brings notable expansion fees that the league and owners share.”

Managing those fees, and so many others, at pro sports franchises falls to accountants, who deal with the day-to-day financials at some of the most glamorous organizations in the country. But those accountants operate the same way accountants do at any other business. Expenses (largely in the form of player salaries) go out, and revenue (stadium sales, merchandising, TV deals) comes in. Sports are, of course, seasonal, so team accountants deal with specialized issues like cash flow forecasts.

Team accountants also play a big role when a team is up for sale. The data we analyzed is a mixture of team sales and purchase prices, and Forbes’ valuations. Since major league teams don’t often change hands, Forbes’ estimates are often the best measure of value. Based on public NFL, MLB, NBA, and NHL team sale prices since 1999, Forbes estimates have been off by an average of less than 16 percent.

According to these valuations, no sport has been better for the net worth of franchise buyers than professional basketball. From 2010 to 2016, the average NBA franchise has jumped 22.66 percent in value annually.

The value of Major League Soccer teams has risen nearly as steeply (22.3 percent annually since 2008), followed by those in Major League Baseball (17.6 percent since 2010), the National Football League (14.8 percent since 2010), and the National Hockey League (14.6 percent since 2010). The gains have enriched more than two dozen new ownership groups.

In the NFL, three teams have been sold over the last six seasons. Four Major League Baseball teams, eight hockey teams, and 12 of the league’s 30 NBA franchises have switched hands over the same period. Some of the buyers—like Haslam—are already cashing in.

Nothing but Net Gains—For Now

Count NBA legend Michael Jordan and Tom Benson among the list of winners. In March 2010, BET founder Robert Johnson sold his interests in the Charlotte Bobcats (now Hornets) to Jordan in a “fire sale” that included just $25 million in cash up front and $275 million total, according to The Daily Beast.

Months later, in December, New Orleans Hornets (now Pelicans) majority owner George Shinn sold his team to the NBA for an undisclosed price, though the league valued the franchise at more than $300 million at the time of purchase. Benson, owner of the NFL’s New Orleans Saints, would take over two years later, paying just $338 million. Today, Forbes values the Hornets at $750 million and the Pelicans at $650 million. Jordan and Benson are sitting on huge gains as a result of buying at bargain prices.

But neither comes close to the league’s biggest financial winner of the last seven years. Former Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald Sterling and his wife were beneficiaries of the team’s $2 billion sale to former Microsoft executive Steve Ballmer in 2014. Sterling purchased the Clippers (then in San Diego) for just $12.5 million in 1981, a compound annual return of 16.6 percent annually over 33 years—the same yearly return as Haslam’s Browns since 2012.

How Recent Performance Creates Pricing Power

So why the soaring values? Sterling—like Haslam, Jordan and Benson—bought his franchise during troubled times. Depressed prices rarely stay that way forever, especially if the overall economics of the surrounding community improve. The Los Angeles of 1981 is a world away from today’s Los Angeles. And Cleveland, while still in the formative stages of an economic resurgence, is enjoying success in other sports.

LeBron James returned to the city and its Cavaliers after four seasons in Miami, and he brought an NBA title with him. A talented Cleveland Indians baseball club took the Chicago Cubs to the brink last year in a World Series that made history. Haslam’s Browns get to bask in the reflective glow of these triumphs, giving fans and corporate backers reason to believe it’s a matter of time before their team re-joins the ranks of the NFL’s elite. (In 2013, local utility FirstEnergy agreed to pay an estimated $6 million annually for at least 17 years for the naming rights to what had been Cleveland Browns Stadium.)

Winning adds value even faster, especially to franchises with a long history of losing. Take the Golden State Warriors. Venture capitalist Joe Lacob and movie producer Peter Guber led a team of investors who purchased the ailing NBA franchise in July 2010 for a then-record $450 million. The investors vowed to build “nothing short of a championship organization,” and five years later Golden State defeated the Cavaliers to capture the team’s first title in 40 years.

The Cavs and Warriors would meet again the next year with Cleveland overcoming a 3-1 deficit to earn the first NBA title in franchise history. Television ratings for both series set viewership highs not seen since 1998, when Jordan was still helping the Chicago Bulls raise banners.

Both teams are far more valuable today as a result of their performances. Specifically, Forbes prices the Warriors at $1.9 billion—a 27.1 percent annualized return for Lacob, Guber and their partners—and the Cavs at $1.1 billion, a 10.3 percent annualized return for principal owner Dan Gilbert, who purchased the team and its home arena for $375 million in 2005.

What the Warriors and Cavs have been to basketball, the Kansas City Royals have been to Major League Baseball. Back-to-back appearances in the World Series culminating in a 2015 win has pushed the team’s fair market value to $865 million, a 14.7 percent annualized return for current owner and former Walmart executive David Glass, who purchased the team for $96 million in 2000.

Giant returns aren’t the only factors for team owners.

“There is very much a psychological and ego issue at play,” said Syracuse’s McKelvie. “The billionaires get to own a professional sports team and hang out with celebrities. Talk about a new shiny object that they could only dream of as kids.”

When Winning Isn’t Everything

But the model of buying a turnaround and then giving shrewd executives the authority to assemble a winning team is rare. The most valuable franchises get that way through a combination of deep roots in a large metropolitan area that draws a huge fan base, lots of broadcast time, and rich licensing opportunities.

The NFL’s Dallas Cowboys top that list with an estimated $4.2 billion in net value. Only two teams get within $800 million of Dallas—the NFL’s New England Patriots and the MLB’s New York Yankees. No other baseball team ranks in the top 10 but two NBA teams—the New York Knicks, tied for fifth at $3 billion, and the Los Angeles Lakers, tied for 10th at $2.7 billion—make the list.

Not surprisingly, four of the top teams are located in the New York City metropolitan area (the Yankees, the Knicks, and the NFL’s Giants and Jets). Two others are in Los Angeles (the Lakers and the NFL’s newly relocated L.A. Rams) with a third in San Francisco (the NFL’s 49ers). Dallas, New England, Washington, D.C., and Chicago (the Bears, tied for 10th with a value of $2.7 billion) round out the list.

Each of those franchises is at least 50 years old, and in most cases, ownership looks a lot like it did decades ago. The only team to have changed hands in the last 10 years—the Rams in 2010—didn’t really change hands. Billionaire Stan Kroenke purchased a small stake in the team in 1995 and then bought the remainder in 2010 as the then-St. Louis based Rams struggled to compete, bringing his “all-in” position to $200 million. Now, back in L.A., Forbes pegs the Rams as worth $2.9 billion.

Today, Forbes puts Kroenke’s personal fortune at $7.4 billion—more than double the $2.9 billion it estimated for him six years ago. Making a bigger bet on the Rams at a low point in the team’s history has made a huge difference in Kroenke’s net worth. The same can be said for Lacob and Guber and their bet on the Warriors. Or Gabriel’s purchase of the Cavs. Or Glass’ purchase of the Royals.

“Price is what you pay, value is what you get,” investor Warren Buffett has famously said. While he was talking about stocks, Buffett’s advice applies to sports franchises as well. Buying at a low point is often the key to earning big returns—whether you’re investing in stocks or, if you’re a billionaire like Jimmy Haslam, the Cleveland Browns. Either way, history says there’s plenty of money to be made.