Unemployment and the Effects of the Minimum Wage

With the “Fight for $15” making headlines, opinions abound about whether raising the federal minimum wage will have a positive or negative effect on unemployment rates. Advocates of an increase cite the impossible task of making ends meet on today’s paltry sum of $7.25 an hour and say an increase would have little effect on the overall economy. Those against such a move predict that doing so would cause employers to lay off more and hire less—raising unemployment rates as a result. As is often the case with such emotionally charged issues, especially in an election year, the broader conversation about the minimum wage tends to involve more feeling than historical fact. To balance such a dynamic, we decided to turn to the data to see what it reveals.

Correlation Between Unemployment and the Minimum Wage

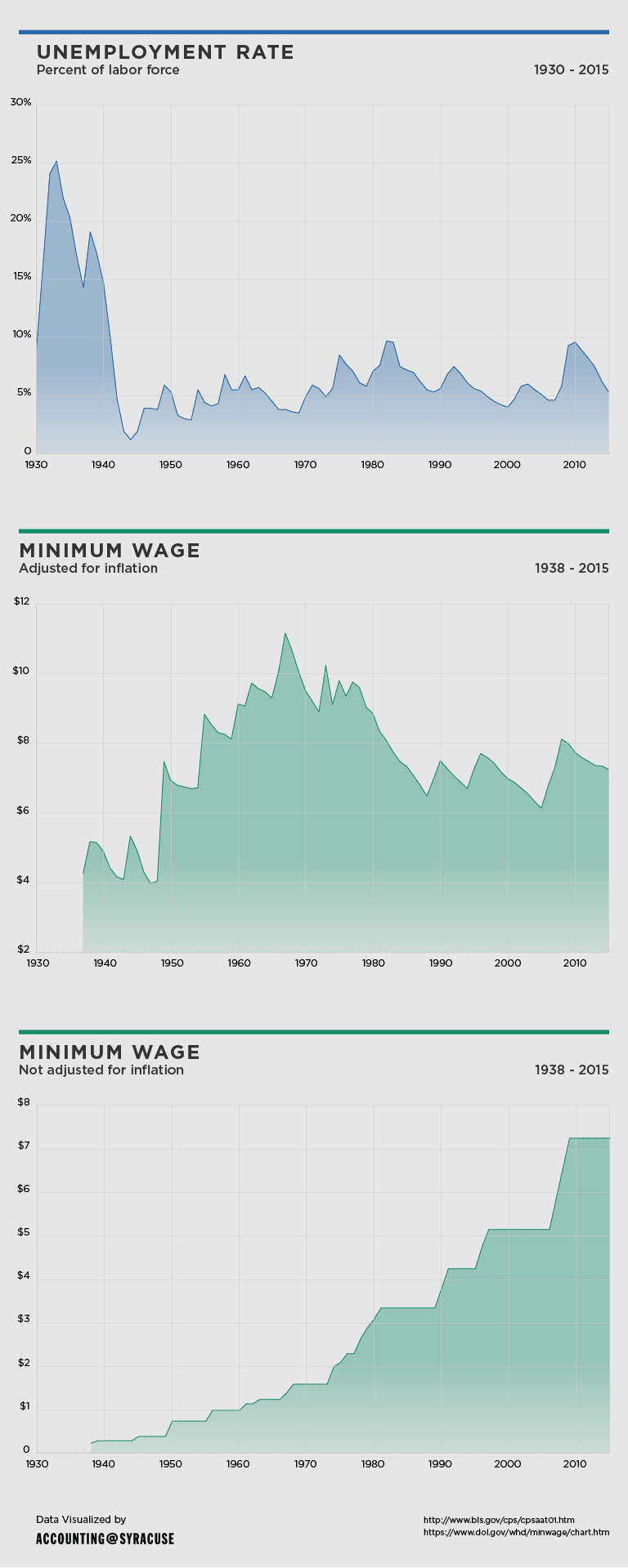

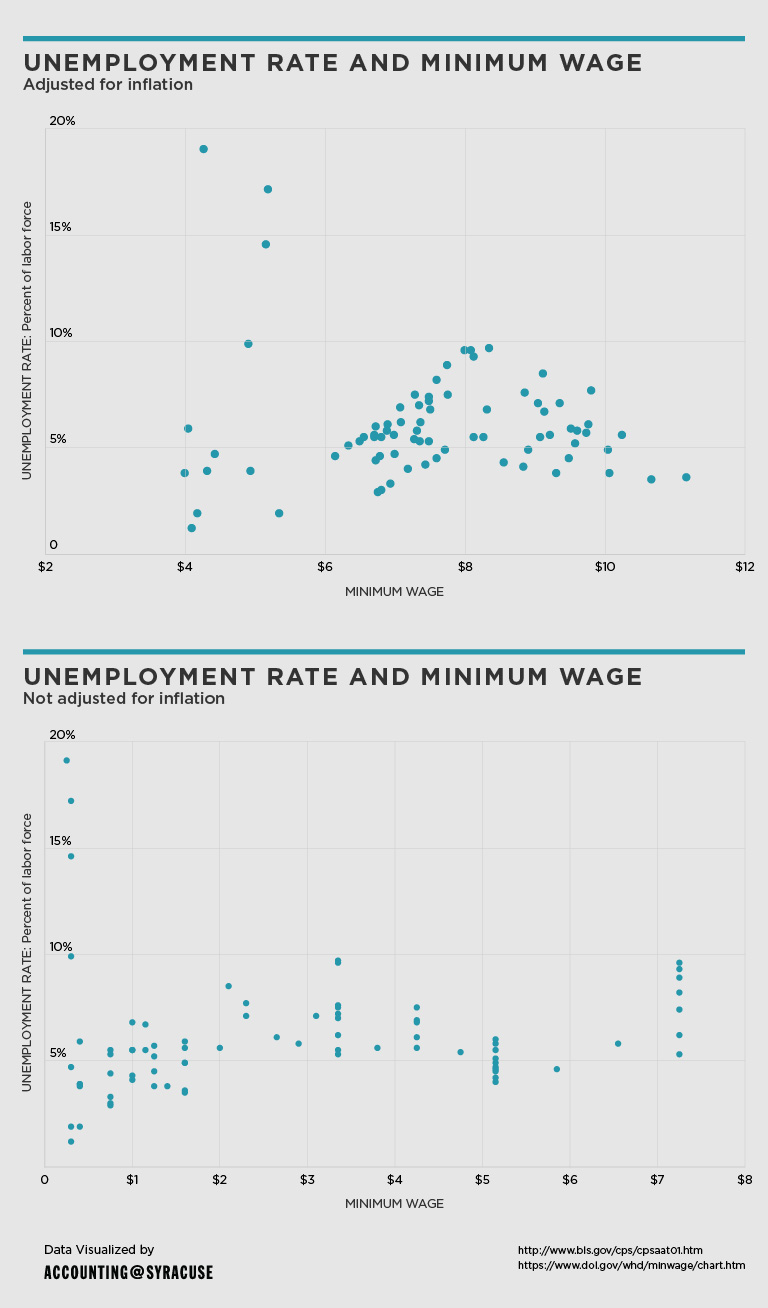

In the series of charts below, we show the history of the federal minimum wage and unemployment since 1930 with visualizations that indicate whether there seems to be any correlation between the two. In one graph, we adjusted the minimum wage for inflation. As you can see on the scatterplots, there appears to be no correlation when adjusting the minimum wage for inflation, and a very slim to no correlation when inflation is not part of the equation. In fact, there are several periods in which unemployment was at some of its lowest levels while employees also enjoyed highs in adjusted minimum wage rates—including the mid-1940s, the late 1960s and our current era. Adjusting for inflation gives a more accurate depiction of the data, since the cost of living has a significant influence on how far a dollar can be stretched at any given time.

Unemployment and the Minimum Wage — Changes by President

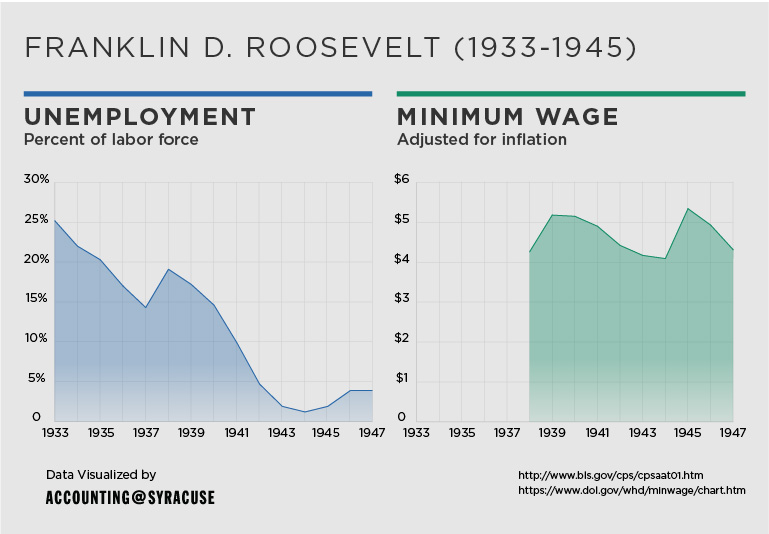

In addition, we’ve provided a picture of trends during six different presidencies that includes the two years after each left office. When Franklin D. Roosevelt entered the White House during the Great Depression, the nation faced some rocky years in terms of unemployment rates. After the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 established the minimum wage, unemployment rates that had started to rise again after recovering from the Great Depression quickly fell to the point at which an inverse relationship between the two began to occur in 1942—with the minimum wage slowly rising and unemployment in a steady decline. In the two years after FDR left office, trends between the two eventually became evenly matched.

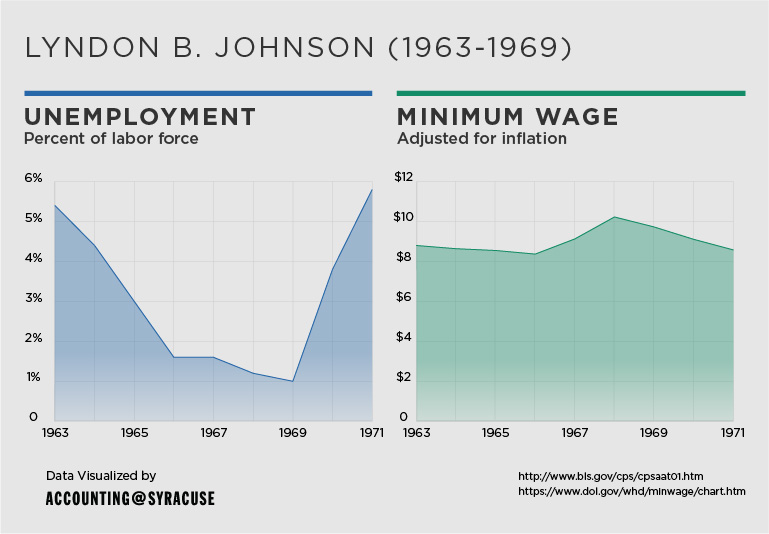

A somewhat similar pattern occurred during Lyndon B. Johnson’s term. Unemployment rates and the amount of the minimum wage trended in the same direction for several years, but then also began to head in opposite directions. Around 1966, as the minimum wage climbed, unemployment rates started to fall.

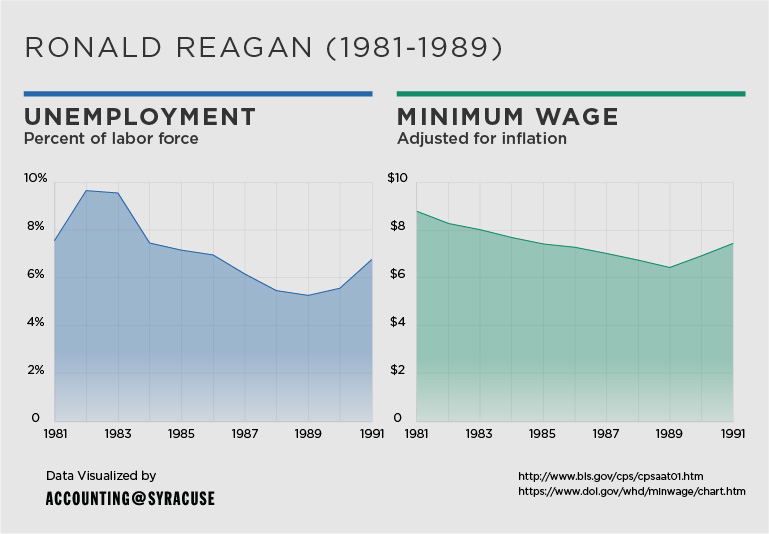

During the early years under Ronald Reagan, unemployment rates rose as the minimum wage fell, then trended along a similar path for the remainder of his administration—falling and rising together for the most part, except for a steep dip in unemployment in the mid-to-late 1980s.

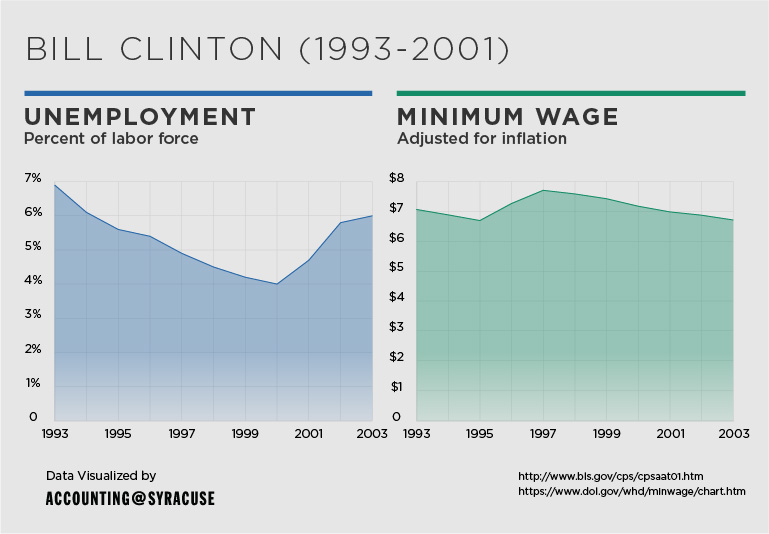

While Bill Clinton was in office, there were also periods in which unemployment rates dropped as the minimum wage rose. In contrast, during the years in which unemployment rose, the minimum wage was on a downward trend.

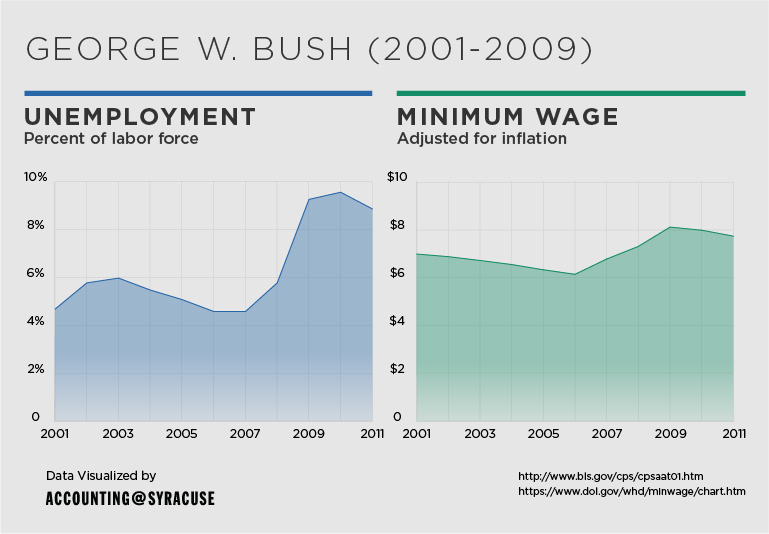

When George W. Bush was president, there was a period starting around 2007 in which unemployment rates and minimum wage rates mirrored each other to some extent—both trending upward and downward together, although the unemployment rates took a more dramatic track.

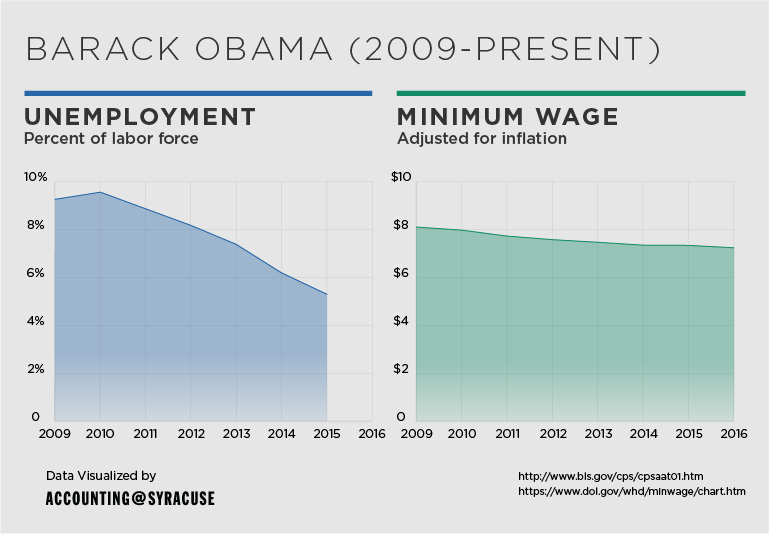

In Barack Obama’s administration, the minimum wage has been on a fairly even keel. The unemployment rate, after climbing slightly at the beginning of his first term, has steadily decreased—with a sharp drop starting in 2015.

Overall, what we see is that while those on both sides of the Fight for $15 may have strong arguments to back up their claims, the data doesn’t seem to reveal a significant and consistent correlation for either camp.

According to Robert Florence, adjunct associate professor at Syracuse University’s Martin J. Whitman School of Management, “Minimum wage exists these days to satisfy purely political goals, because it doesn’t have any economic basis. The real problem with workers not garnering higher incomes for much of their working lives lies in their lack of education, which is primarily a problem among the poor. The minimum wage is not the solution. A better education system is.”

Instead of a single conclusion, perhaps the reality is more likely to be found somewhere in the middle.