Muckraking and Investigating: The Reporters Who Uncovered Government Secrets and Scandals

At the turn of the 20th century, a 47-year-old reporter finished a 19-part series of stories that would bring down an oil monopoly and the reputation of the tycoon who founded the company. Ida Tarbell not only exposed the questionable business practices of John D. Rockefeller, she also ushered in a new era of journalism: investigative reporting.

Tarbell and other “muckrakers” continued to uncover the corruption in city governments and industry, and the American public couldn’t get enough. Tarbell brought down Standard Oil. Upton Sinclair exposed the unsanitary and inhumane practices of the meatpacking industry. Lincoln Steffens went from city to city to expose corruption at the local level. The drive to find and expose corruption fueled both journalists and newspaper sales. It also challenged the public to take a closer look at government and industry.

Today, investigative journalists continue to unearth and shine light on deceitful practices. In-depth and thoughtful reporting is a check to ensure American democracy works in the best interest of the people. Throughout American history, journalists have fought to educate and inform the public of the actions taken by elected officials. Without investigative reporting, the American public would never have learned of the abuses that happened in Abu Ghraib, President Nixon’s cover up of Watergate, or the truth behind American involvement in the Vietnam War.

At a time when politicians spread inaccurate information and have declared a “war on media,” the country relies on journalists to uncover the truth and hold elected officials accountable. Below are examples from the present back to the 1950s of times when journalists changed the course of American history by exposing lies and covert actions taken by the government.

2013: Edward Snowden Exposes NSA Surveillance

The Guardian and The Washington Post published a series of articles on American surveillance methods detailed in leaked documents provided illegally by Edward Snowden, a contractor with the U.S. government. The documents revealed that the National Security Agency (NSA) had been collecting data on American citizens and monitoring emails, phone records and instant messaging.

In 2014, The Washington Post was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service “for its revelation of widespread secret surveillance by the National Security Agency, marked by authoritative and insightful reports that helped the public understand how the disclosures fit into the larger framework of national security.”

2005: Domestic Spying without a Warrant

A New York Times story by James Risen and Eric Lichtblau detailed the secret authorization of warrantless monitoring authorized by President George W. Bush. The administration gave approval for the NSA to intercept calls and emails of individuals inside the United States without a warrant. The New York Times delayed publishing the story for a year after the White House argued that publication would jeopardize continuing investigations. Additional reporting was conducted during that year.

In 2008, Congress overhauled the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act to require broad warrants to conduct emergency wiretaps on American citizens. The deal also provided legal immunity to the phone companies that had cooperated with the warrantless eavesdropping program.

2003: Inhumane Treatment at Abu Ghraib

On Nov. 1, Charles Hanley of The Associated Press reported human rights violations inside a U.S. military prison in Iraq called Abu Ghraib. The firsthand accounts told to Hanley by released detainees matched previous reports of abuse that had been documented by human rights organization Amnesty International.

After an investigation by the U.S. Central Command, 17 soldiers were suspended for their actions at the prison. In April 2004, photos of the abuses were shared in a “60 Minutes II” piece on CBS. The Washington Post later found documents showing authorization to loosen the rules regarding methods used on detainees. The order came from Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez and included methods that made the U.S. Central Command “object International human rights advocacy organization, Human Rights Watch called it “a clear violation of the Geneva Conventions.” Eleven American soldiers were convicted of crimes related to the abuses at Abu Ghraib.

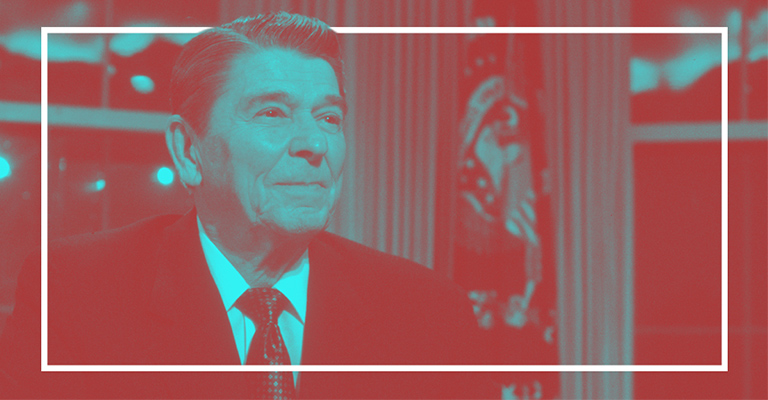

1986: The Iran-Contra Affair

On Nov. 3, a Lebanese news magazine called Ash-Shiraa reported on a leak from an Iranian radical about covert arms deals made to Iran in exchange for the release of American hostages. The money from those deals went to fund the Contra rebels, an anti-communist insurgent group in Nicaragua. The next day, The New York Times ran the story on the front page.

By participating in the arms deal, the Reagan administration had violated an embargo, which specifically prohibited weapons sales with Iran. This happened while seven Americans were held hostage by an Iranian group in Lebanon. The trade came in stark contrast to President Reagan’s strong declaration, “America will never make concessions to terrorists.” A congressional investigation concluded that Reagan bore ultimate responsibility for the arms deal despite having no knowledge of the actions taken by his national security advisors.

1974: Watergate

On June 17, 1972, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post were assigned to report on a burglary at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate building in Washington, D.C. Through investigative reporting and with information provided by an anonymous source known as Deep Throat, Woodward and Bernstein uncovered information tying the break-in and attempts to cover it up back to President Richard Nixon’s re-election campaign. Nixon denied any involvement in the scandal.

A Senate committee was formed to investigate Watergate. During a Senate hearing, it was revealed that Nixon recorded every conversation that happened in the Oval Office and the Cabinet Room of the White House. The tapes were subpoenaed, and Nixon refused to release the tapes. When the tapes were eventually released, investigators learned that 18.5 minutes had been erased from one of the key tapes. President Nixon resigned on Aug. 8, 1974, after the House Judiciary Committee recommended his impeachment. To this day, new evidence on the Watergate investigation is still being uncovered, and scandals are often compared to Watergate by being given the suffix “-gate.”

1971: Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers

While covering the Vietnam War for The New York Times, Neil Sheehan received a classified government study from a RAND research analyst, Daniel Ellsberg. The study revealed the U.S. government had lied about the purpose and extent of its role in Vietnam during the Johnson Administration. This study was dubbed the “Pentagon Papers.”

On June 13, 1971, The New York Times ran a series of daily articles based on the Pentagon Papers. After the third article, The Nixon Administration got a temporary restraining order against publication of the information citing national security as the reason for secrecy. The New York Times joined forces with The Washington Post and fought the government’s attempts to continue covering up its involvement in Southeast Asia. On June 30, the Supreme Court ruled that publication of the papers was allowed under the First Amendment.

1969: Mỹ Lai Massacre

On Nov. 12, 1969, Seymour Hersh broke the story of the Mỹ Lai Massacre after extensive interviews with Second Lieutenant William Calley, the commanding officer for the 1st Platoon, Charlie Company of the Americal Division’s 11th Infantry Brigade.

On March 16, 1968, Charlie Company was sent on a search-and-destroy mission into the Mỹ Lai hamlet, part of the village of Son Mỹ in Vietnam. This was reported in Stars and Stripes with the headline “U.S. infantrymen had killed 128 Communists in a bloody daylong battle,” however in reality American soldiers murdered unarmed Vietnamese men, women and children. While there is not a definitive body count, the number of civilians killed at Mỹ Lai is estimated between 347 and 504.

In 1970, Hersh was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting “for his exclusive disclosure of the Vietnam War tragedy at the hamlet of Mỹ Lai.” Following Hersh’s article, the Army ordered a special investigation into the Mỹ Lai Massacre and the subsequent cover-up. Though Calley claimed he was following orders, he was convicted and sentenced to life in prison on March 29, 1971. Two days later, President Richard Nixon released Calley to house arrest. In September 1974, Calley was released on parole.

1953: McCarthyism and the Red Scare

In the early 1950s, during what became known as the Red Scare, Senator Joseph McCarthy actively investigated allegations of communists and communist-sympathizers in the United States. He alleged that members of the Army at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, were covert communists, and 42 people were suspended without pay. Murrey Marder of The Washington Post investigated McCarthy’s statements during what became known as the Army-McCarthy Hearings. After spending a week at Fort Monmouth, Marder learned that most of the allegations had previously been investigated and dismissed by the Army. After being questioned by Marder at a news conference, Army Secretary Robert T. Stevens admitted that there was no evidence of spying at Fort Monmouth.

Citation for this content: Syracuse University’s Online Master’s in Communications program